Lesson 1: Different Brains

Trading Card: Brainium

Artist's name sought

Lesson notes from YTA Founder: The main message in this lesson is that thinking is accomplished by a brain, and since each child has an amazingly complex and powerful type of brain, why not use it and become a Thinker! Since it is the first YTA lesson as well, I usually begin with a brief discussion about the YTA program. I state that we need more American children to become science and technology professionals. Then the children are asked to provide examples of why this is the case (for example to cure disease or track and destroy asteroids).

Following this brief discussion, I ask the students for the meaning of the word "brain". It is great to see them think about a word they use very often but have not thought much about defining in words. I guide the discusion towards determining how we know when something has a brain (an ant for example). Usually the conclusion is that if something reacts to a stimulus in the outside world (ant changes directions when a foot is stamped near it) than we can all agree that it has a brain. This consensus building, or agreement on rules for accepting a conclusion, is a big part of scientific progress, which rarely occurs based on 100% confidence in conclusions or 100% agreement on the conclusions. Thus in a number of YTA lessons we build a consensus to establish a rule that we write on the board for future reference when we want to judge a conclusion or experimental result.

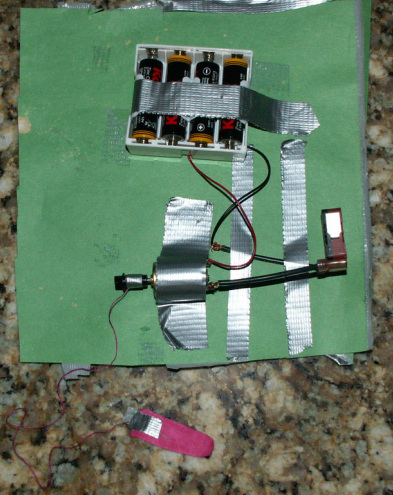

I then bring out the "turtle". The turtle is constructed using a motor from a model kit, electric switch, and battery pack, all connected with wires and taped to and sandwiched between two pieces of construction paper. I use the motor and battery pack found in the Toys R Us Deluxe Scientist Kit I purchased. I purchased the electric on-off switch at Radio Shack, selecting one that could be taped to a piece of construction paper and pressed from the top to activate. I attach a string to the axle in the motor with a "tongue" at the other end of the string. The tongue sticks out of the construction paper and is the only part of the inner workings of the turtle that can be seen by the children. When I press on the turtle at the place the switch is located, the motor turns on and the tongue is pulled into the turtle. So when the turtle is searching for food with its tongue, and an elephant steps on it (the stimulus) the turtle reacts by pulling in its tongue, proving, according to our agreed upon definition, that the "turtle" has a brain. And then the fun part; we break out the scissors and perform a dissection to study this creatures brain. Making the turtle can be a little challenging, but after I made my turtle and taped its "brain" to one piece of construction paper, I have used the same one for years. Between each lesson I just change the top piece of construction paper (the piece that was cut up during the dissection). It would be fine to make a different creature that responds to a stimulus, so long as the "brain" is hidden and a dissection can be performed to study the operation of its brain. As with all YTA lessons, children should be encouraged to think; that is to suggest solutions to problems the instructor poses and to take turns repeating the logical explanation underlying observations and data, for example the operation of the dissected turtle brain:

Following this brief discussion, I ask the students for the meaning of the word "brain". It is great to see them think about a word they use very often but have not thought much about defining in words. I guide the discusion towards determining how we know when something has a brain (an ant for example). Usually the conclusion is that if something reacts to a stimulus in the outside world (ant changes directions when a foot is stamped near it) than we can all agree that it has a brain. This consensus building, or agreement on rules for accepting a conclusion, is a big part of scientific progress, which rarely occurs based on 100% confidence in conclusions or 100% agreement on the conclusions. Thus in a number of YTA lessons we build a consensus to establish a rule that we write on the board for future reference when we want to judge a conclusion or experimental result.

I then bring out the "turtle". The turtle is constructed using a motor from a model kit, electric switch, and battery pack, all connected with wires and taped to and sandwiched between two pieces of construction paper. I use the motor and battery pack found in the Toys R Us Deluxe Scientist Kit I purchased. I purchased the electric on-off switch at Radio Shack, selecting one that could be taped to a piece of construction paper and pressed from the top to activate. I attach a string to the axle in the motor with a "tongue" at the other end of the string. The tongue sticks out of the construction paper and is the only part of the inner workings of the turtle that can be seen by the children. When I press on the turtle at the place the switch is located, the motor turns on and the tongue is pulled into the turtle. So when the turtle is searching for food with its tongue, and an elephant steps on it (the stimulus) the turtle reacts by pulling in its tongue, proving, according to our agreed upon definition, that the "turtle" has a brain. And then the fun part; we break out the scissors and perform a dissection to study this creatures brain. Making the turtle can be a little challenging, but after I made my turtle and taped its "brain" to one piece of construction paper, I have used the same one for years. Between each lesson I just change the top piece of construction paper (the piece that was cut up during the dissection). It would be fine to make a different creature that responds to a stimulus, so long as the "brain" is hidden and a dissection can be performed to study the operation of its brain. As with all YTA lessons, children should be encouraged to think; that is to suggest solutions to problems the instructor poses and to take turns repeating the logical explanation underlying observations and data, for example the operation of the dissected turtle brain:

Next I ask one of the children to give a stimulus to me by stepping on my foot, after which I yell, "Ow!!". The class then concludes, based on our definition, that I have a brain. We joke about dissecting my brain, and then I show them a 3-D model of the head in which the skull comes off to show the brain (see supplies picture below). I next give them printed hand outs with pictures of a real brain showing the folds of the cortex, and pictures of a brain through a microscope showing neurons with long branches.

We discuss neurons, mentioning that they are connected to each other like the wires in the turtle's brain, to allow our brain to think and perform other functions. I then hand out clay (I purchase a bucket of clay at CVS) and guide the students, usually in groups, to make a neuron with a relatively long axon.

After this I show the students a large piece of brown paper cut out to be in the shape of a small person. I tell the students that I have made a chef but have forgotten his brain, and I am concerned that he will not pull his hand away from the hot stove when he touches it. I the guide the students to make a 2 neuron reflex loop in which a sensory neuron senses the hot stove in a finger and through its axon brings the signal back to the spinal cord. In the spinal cord the electrical signal activates the next neuron in the circuit which goes back to the arm to activate a muscle (also made of clay), pulling the arm away from the hot stimulus. When complete I ask a few of the students to describe what happens when the painful stimulus is applied, using the scientific terms including the key words for this lesson; brain, neuron, axon, signal, muscle.

Next we make a more complex circuit, where a puff of air precedes the hot stimulus, so that the brain in the head (cerebrum) can learn to predict that the heat is coming and send a signal down to the spinal cord to pull the muscle away before the heat is even applied. The YTA instructor will need to judge how much guidance to give in the construction of this simple nervous system. The important part is to leave time to have the discussion at the end where the students take turns explaining what happens in this creature after a puff of air is applied.

The lesson ends with a discussion of the other things, beyond reflexes, that our brain must accomplish. At some point I note that the brain must need alot of neurons and ask the children how many neurons our brain has (10-100 billion with alot in the head). I conclude by asking the students why we need THAT many neurons in our brain, leading them to the conclusion that it is so they can be great thinkers.

We discuss neurons, mentioning that they are connected to each other like the wires in the turtle's brain, to allow our brain to think and perform other functions. I then hand out clay (I purchase a bucket of clay at CVS) and guide the students, usually in groups, to make a neuron with a relatively long axon.

After this I show the students a large piece of brown paper cut out to be in the shape of a small person. I tell the students that I have made a chef but have forgotten his brain, and I am concerned that he will not pull his hand away from the hot stove when he touches it. I the guide the students to make a 2 neuron reflex loop in which a sensory neuron senses the hot stove in a finger and through its axon brings the signal back to the spinal cord. In the spinal cord the electrical signal activates the next neuron in the circuit which goes back to the arm to activate a muscle (also made of clay), pulling the arm away from the hot stimulus. When complete I ask a few of the students to describe what happens when the painful stimulus is applied, using the scientific terms including the key words for this lesson; brain, neuron, axon, signal, muscle.

Next we make a more complex circuit, where a puff of air precedes the hot stimulus, so that the brain in the head (cerebrum) can learn to predict that the heat is coming and send a signal down to the spinal cord to pull the muscle away before the heat is even applied. The YTA instructor will need to judge how much guidance to give in the construction of this simple nervous system. The important part is to leave time to have the discussion at the end where the students take turns explaining what happens in this creature after a puff of air is applied.

The lesson ends with a discussion of the other things, beyond reflexes, that our brain must accomplish. At some point I note that the brain must need alot of neurons and ask the children how many neurons our brain has (10-100 billion with alot in the head). I conclude by asking the students why we need THAT many neurons in our brain, leading them to the conclusion that it is so they can be great thinkers.

Lesson 1 Plan

| different_brains.pdf | |

| File Size: | 220 kb |

| File Type: | |

Lesson 1 Trading Card

| lesson_1_trading_card.pptx | |

| File Size: | 1812 kb |

| File Type: | pptx |

Lesson Handout

| different_brains_handout.ppt | |

| File Size: | 1465 kb |

| File Type: | ppt |